Introduction

AM Academy is grateful to announce a series of articles on nanoparticle synthesis. Nowadays, a breakthrough is happening in nanotechnology, revolutionizing the way we live. Nanoparticles are finding their way into numerous applications in electronics, optics, aerospace, coatings, consumer care, pharmaceuticals, and many more.

With this series, AM Academy will tell our readers the story of nanoparticles: What are they? How did people start looking at matter on that scale? What defines the remarkable properties of nanoparticles, which are often drastically different from those of the bulk material? We will provide an overview of general approaches to nanoparticle synthesis, control over their size, shape, morphology, and arrangement, and touch on the most remarkable applications of nanoparticles. Through the series, AM Academy will highlight the opportunities that the continuous flow reactors of the K-series bring to the field.

Our sincere intention is to tell the story in simple, easy-to-understand language. However, we believe that even those skilled in the art will find new facts and original approaches here, inspiring imagination and giving birth to new developments.

This chapter introduces you to nanoparticles and gently touches on the history of humanity’s interaction with, approach to, and beginning to study the subject.

Please enjoy.

Nanomaterials Everywhere

The name “nanoparticle” was coined from the Greek word νάνος (nanos), meaning “dwarf.” In a list of SI metric prefixes, “nano” stands for 10⁻⁹, or 0.000,000,001. It was introduced relatively recently, in 1960, which is a good indication of a time when people started dealing with this scale often enough. Ironically, the word “particle” originates from the Latin particula, meaning “a small part.” Therefore, a nanoparticle is a “dwarfed small part” of matter that has nanometre-scale features (in the range from 1 to 100 nm) in at least one dimension. It is within this very size range where qualitative changes occur in the physicochemical properties of substances and materials.

As Earth makes its way around the Sun, it passes through a zodiacal dust cloud. Thousands of tons of this cosmic dust reach Earth’s surface every year, many of which are in the nm size range. Cosmic dust has minimal impact on our daily lives, but this is not true for another natural source of continuous nanoparticle supply. Volcanic ash contains numerous toxic metals, including lead, mercury, cadmium, and many others. To make matters worse, the concentration of toxic metals in the nanoscale fraction of volcanic ash has been found to be 100 to 500 times higher than in larger particles, and nanosized volcanic ash reaches the stratosphere, affecting the global environment for years after an eruption.

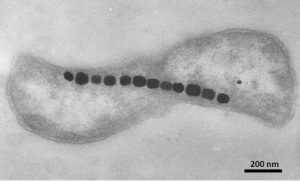

On the bright side, nanoparticles are routinely produced by many living organisms, often performing very important and unique functions. To mention a few, the most wonderful functional food developed by Mother Nature, mammalian milk, contains casein micelles—aggregates of milk protein molecules organized around ~200 nm droplets of milk fat that stabilize them from separation. These micelles play a crucial role in making nutrients easily available for absorption and contribute to babies’ development. On the other side of the evolutionary tree, magnetostatic bacteria produce iron oxide or iron sulphide nanoparticles that act as a natural compass, helping them navigate toward oxygen-poor sediments beneficial to their metabolism.

First Synthesis

Being a common phenomenon in nature, nanoparticle synthesis is not such a novel subject of conscious human activity. Probably, the very first conscious social activity in the long progression from australopithecines to Homo erectus to Homo sapiens was cooking. It is logical to assume that the first-ever synthesized nanoparticle was created in a cooking pot. At the very least, the oldest existing cookbook, a collection of Roman cookery recipes called Apicius, completed around the third century AD, describes combining oil with vinegar and fish sauce to produce what was likely the first mayonnaise. Mayonnaise is an emulsion in which a nanometre-thick shell made of lecithin molecules is organized on the surface of micron-sized oil droplets dispersed in water, creating a smooth, creamy texture.

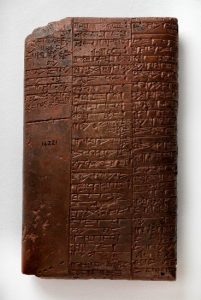

Another human practice developed from prehistoric times was cleansing. The earliest known chemical process is recorded on a Sumerian clay tablet, which describes heating a mixture of oil and wood ash to produce soap for washing woollen clothing. The cleaning agents in soap water (molecules of fatty acids) organize themselves into nanometre-sized aggregates called micelles. These micelles can remove dirt, grease, oils, faecal particles, and more from skin or hair.

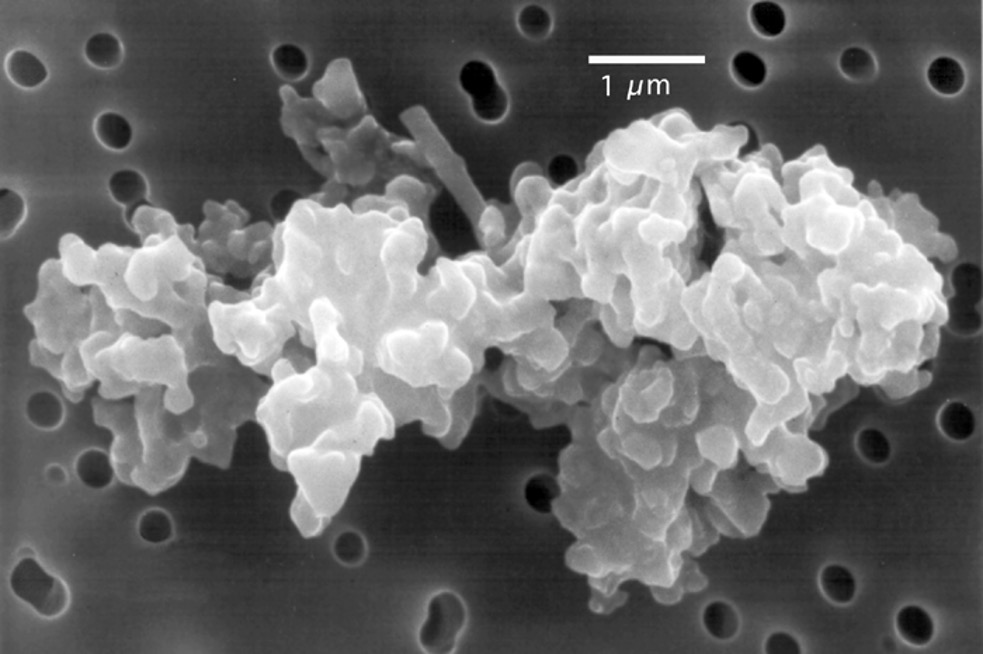

The first inorganic synthetic nanoparticles were most likely produced as part of the process of making dyes and pigments. People across the globe began developing tattooing techniques for both decorative and therapeutic purposes as early as the Neolithic era (10,000–2,000 BC). The common dye for early tattooing practices was soot. For example, soot was used to make therapeutic tattoos on the 5,300-year-old Tyrolean Iceman. Chemical analysis of the dye suggested the soot was scraped off rocks surrounding a fireplace. Ornamental tattoos found on the hands and legs of a 1,000-year-old Peruvian mummy were also made of soot, which consists of tiny carbon particles. The particles making the Peruvian mummy’s tattoo were 10 nm in size.

Early Industries

Unique dyes containing nanoparticles of silver, gold, and their alloys were developed by the Romans to stain glass. Glass production grew rapidly in the Roman Empire from around the 1st century AD, following the development of glass-blowing techniques. A masterpiece of Roman decorative glass is the Lycurgus Cup, which changes color when light passes through. The glass contains a tiny fraction of bimetallic particles (the Ag:Au ratio was about 8:1) measuring 70 nm. We do not know the process Roman glassmakers used to produce those nanoparticles and incorporate them into the glass. Most likely, the process was discovered through accidental contamination of sand with ground gold and silver dust, and was not well understood or controlled. Since then, gold, silver, and copper nanoparticles have been used for staining European glass and Chinese ceramics to create lustrous effects. Nanoparticles were produced from a mixture of metal salts or oxides deposited onto the surface of ceramics or glass upon heating in a reducing atmosphere achieved by burning wood or other smoking substances.

It was the lucrative field of making stained glass and ceramics for the wealthy and noble that turned the art of making nanoparticles into science and gave rise to the first works in the field now known as colloid science. Colloid science studies the dispersion of submicron particles in a continuous medium and interfacial phenomenon. To give you a sense of the first scientific works in the area, let us cite an excerpt from a book published by German alchemist Johann Christian Orschall in 1684 that describes the production of ruby glass (in English translation):

“Dissolve finely beaten gold flakes in aqua regis, this is aquafort in which salmiac (ammonium chloride) had been dissolved. One obtains upon desiccation a yellow residue which is water soluble. In acidic condition it is termed solution auri. … Take a large glass full of pure well water and add dropwise a few drops of the solution auri. Then place a piece of cleanly scraped English tin into the glass. If it is left therein for some time it will look quite black, but after a few hours it begins to colour the water red and finally the water reaches maximum brilliancy. The tin is then removed. … I take this gold sol precipitated by the tin and mix it thoroughly with six parts of Venetian glass talc, grind carefully, mix with my silica, and upon melting obtain the most beautiful ruby glass flux…”.

Scientific Beginnings

The first systematic study of inorganic colloids was published by Italian chemist Francesco Selmi between 1845 and 1850. He studied aqueous dispersions of AgCl, colloidal sulfur, and Prussian blue dye (Fe₃₄[Fe²⁺(CN)₆]₃), clearly stating that these compounds cannot exist in the form of molecules or ions but still resemble solutions. Michael Faraday published a paper in 1857 on ruby-red aqueous gold, or aurum potabile (“drinkable gold” in Latin), concluding that it had no indication of dissolved gold but contained well-separated solid particles that were “so finely divided that they pass easily through ordinary filters.” Thomas Graham studied the diffusion of gases and liquids in the 1860s. He realized that some substances (such as starch and gelatin) in solution diffuse very slowly or not at all, compared to others. Solid particles of those substances adsorb all of the solvent, preventing the mixture from flowing. From his observations, he coined the terms “colloid” (from Greek words kolla, meaning “glue,” and eidos, meaning “like”) and “gel” (from Latin gelata, meaning “frozen”) as opposites to “sol” (solution-like).

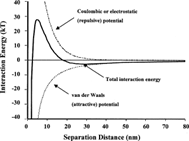

Many generations of scientists were intrigued by the reason behind colloidal stability: What are the forces that stop fine solid particles from coagulating (aggregation that leads to the formation of large coarse particles and their precipitation)? The question remained unanswered until two groups of scientists, Boris Derjaguin and Lev Landau in 1941, and Evert Verwey and Theodoor Overbeek in 1948, independently developed a theory explaining electrostatic colloidal stability (the DLVO theory):

When two same charged particles approach each other, electrostatic repulsion increases but Van der Waals attraction increases also though at a different pace. As a result, there is an energy barrier that forces particles to rebound after a contact. However, this barrier needs to be greater than the thermal energy of particles. Otherwise, particles will overcome the barrier and aggregate. It is the height of the barrier that defines how stable the colloidal system is.

Another group of scientists—Hesselink, Vrij, and Overbeek—developed the theory of steric stabilization in 1971. They considered the contact between uncharged particles with an adsorbed layer of polymer or surfactant molecules on their surface. When such particles approach each other, the concentration of these molecules increases in the region between them. This is energetically unfavourable, as it leads to a decrease in the system’s entropy (e.g., due to the loss of possible molecular conformations).

Birth of Nanotechnology

In 1959, American theoretical physicist Richard Feynman gave a lecture at the American Physical Society titled “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom: An Invitation to Enter a New Field of Physics.” In it, he proposed focusing on manipulating matter at the atomic or nano scale to build devices from the bottom up. Today, this lecture is widely regarded as the birth of the new field of nanotechnology, which studies, manipulates, and engineers matter on the nanometre scale. Like any newborn, this event went largely unnoticed at first, but it took time and many developments before its power became evident. Eventually, hordes of scientists and large amounts of funding propelled the field beyond its horizon.

What’s Next

In the next chapter, we will explore what makes this unique size range, where the matter changes its physicochemical properties, and where the boundaries between homogeneous and heterogeneous phases become blurred.

References

Please find below a list of literature that inspired this piece, for your attentive reading:

- Nanoparticles of volcanic ash as a carrier for toxic elements on the global scale. Chemosphere 200 (2018) 16e22

- Different staining substances were used in decorative and therapeutic tattoos in a 1000-year-old Peruvian mummy. Journal of Archaeological Science 37 (2010) 3256e3262

- Distinguishing Genuine Imperial Qing Dynasty Porcelain from Ancient Replicas by On-Site Non-Invasive XRF and Raman Spectroscopy. Materials 15 (2022), 5747

- Nanoscale engineering of gold particles in 18th century Bottger lusters and glazes. PNAS 119 (2022) e2120753119

- The historical background of colloid chemistry. Journal of Chemical Education May 1950, 264-266.